Tompkins’s work, was one of the century’s major artistic accomplishments, giving quilt-making a radical new articulation and emotional urgency. I felt I had been given a new standard against which to measure contemporary art.

Rosie Lee Tompkins was a pseudonym, adopted by a fiercely private, deeply religious woman, who as her work received more and more attention, was almost never photographed or interviewed. She was born Effie Mae Martin in rural Gould, Ark., on Sept. 9, 1936.

Tompkins was an inventive colorist whose generous use of black added to the gravity of her efforts. She worked in several styles and all kinds of fabrics, using velvets — printed, panne, crushed — to gorgeous effect, in ways that rivaled oil paint. But she was also adept with denim, faux furs, distressed T-shirts and fabrics printed with the faces of the Kennedy brothers, Martin Luther King Jr. and Magic Johnson.

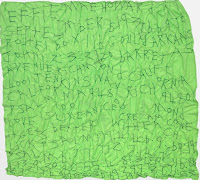

A typical Tompkins quilt had an original, irresistible aliveness. One of her narrative works was 14 feet across, the size of small billboard. It appropriated whole dish towels printed with folkloric scenes, parts of a feed sack, and, most prominently, bright bold chunks of the American flag. What else? Bits of embroidery, Mexican textiles, fabrics printed with flamenco dancers and racing cars, hot pink batik and, front and center, a slightly cheesy manufactured tapestry of Jesus Christ. It seemed like a map of the melting pot of American culture and politics. Sometimes the embroidery reflected her daily Bible reading, including the Gospels, as did her addition of appliqué crosses. Occasionally she stitched the addresses of the places she had lived, and Eli’s home. The information suggested talismanic properties, perhaps prayers. She also said they were meant to improve the relationships between the people evoked by the numbers.

As an artist, Tompkins may have taken improvisation further than other quilters. She all but abandoned pattern for an inspired randomness with an emphasis on serial disruptions that constantly divert or startle the eye — like the badge of a California prison guard sewn to an otherwise conventional crazy quilt. Another narrative quilt is more like a wall-hanging, or maybe a street mural, pieced with large fragments of black and white fabric and T-shirts printed with images of African-American athletes and political leaders. Rows of crosses made from men’s ties evoke the pressures of succeeding while black in American.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/26/arts/design/rosie-lee-tompkins-quilts.html

Caley: Howardena Pindell

| Megan: Joan Mitchell Ethan: Sanford Biggers |

The quilt, vernacular object par excellence, proved to be rich terrain for what Mr. Biggers calls “material storytelling.” As the full scope of his quilt work comes into view, it sheds new light on his long-held concerns — with the Black experience, American violence, Buddhism and art history — and reveals interior dimensions of his personal journey.

Mr. Biggers made his first two quilt works in 2009, installing them at Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. One of the vintage quilts had a flower pattern; the other was plaid. On each, he transposed from a historical map the locations of the church and safe houses from the Underground Railroad, marked them like stars in a constellation, and connected them with charcoal and oil stick.

The reference was to a theory that holds that people along the Underground Railroad shared crucial information in code through quilts hanging at safe houses and other way points. Scholars have found little validating evidence, but for Mr. Biggers, the fact of folk knowledge, even when it’s apocryphal, has worth in itself. “It’s more important that the story endures,” he said. The quilts, however, continue. Their softness is their strength. Their transmittal attests to survival; whether they broadcast freedom codes during the Underground Railroad or not, an artist can inscribe them now with salutary information for today.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/14/arts/design/sanford-biggers-quilt-bronx-museum.html

Sanford Biggers

Veronica: Sam Gilliam-Basquiat, Hanna: Grace Hartigan

Sam Gilliam Paintings

Laura: Howardena Pindell. Serena: Howardena Pindell

No comments:

Post a Comment